Racial health inequalities in London are not new. While racism and discrimination have shaped health outcomes for Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities for decades, awareness and evidence has grown since the 1970s.

The establishment of the NHS and the arrival of the Windrush Generation and migrants from Asia, Africa and beyond brought greater diversity to the city, but also highlighted barriers to

care. As access improved, previously hidden disparities in disease prevalence and outcomes became more visible.

Over time, targeted interventions – such as culturally informed care for sickle cell disease which is more prevalent in people with African or Caribbean heritage – have begun to build momentum in London, showing how tailored approaches can reduce inequalities.

Racism as a public health priority

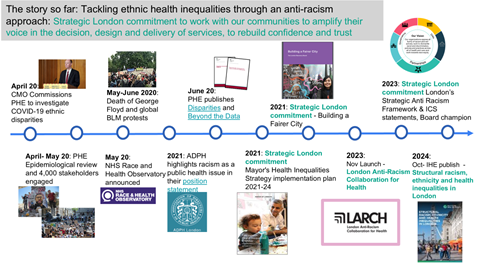

In 2020, two events prompted an overdue focus on ethnicity related health inequalities and the impact of structural racism – ie. the discrimination and disadvantage built into many of our structures, systems and institutions. The Covid-19 pandemic brought the whole world to a halt, and the national health and care system to the brink of collapse. Almost from the outset, it was clear that Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic Londoners were bearing the brunt of the disease, being more likely to become hospitalised and more likely to die with the Covid-19 virus.

The pandemic’s devastating impact was heightened by the toll it took on London’s highly diverse health and social care workforce; 45% of NHS staff in London identify as being of Black, Asian, or minoritised ethnic heritage. During the first wave in 2020, 64% of all nurses and support staff who died during the pandemic were from minoritised ethnic groups, with the number rising to 95% for doctors.

The summer of 2020 also saw the murder of George Floyd, sparking protests across the world and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. These protests fuelled new discourse on structural and systemic racism – bringing greater acknowledgement of the negative impacts of social and environmental inequities on many facets of life for minoritised ethnic groups. It also saw greater recognition that designing solutions for these complex problems requires collaboration – not only across sectors, but also in genuine partnership with those most affected by discrimination.

The response to these events from the health and care sector was wide-ranging. At an operational level, a new wave of co-produced health interventions delivered positive results, with campaigns tackling vaccine hesitancy in Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic groups seeing particular success.

At a more strategic level, significant developments were also taking place, including:

● The Association of Directors of Public Health London (ADPHL) publishing a position statement identifying racism as a public health issue (2021).

● Public Health England publishing two major reports into the impact of the pandemic on minoritised ethnic groups, Disparities (2020) and Beyond the Data (2020).

● The establishment of the independent NHS Race and Health Observatory (2021).

Learning from the pandemic and building a more equitable London

Recognising the urgency of reducing racial health inequalities, the Mayor of London developed a set of major strategic commitments in response..

The Mayor’s Health Inequalities Strategy Implementation Plan (2021) set out a bold vision for collaborative programmes addressing many of the social determinants that underpin racial health inequalities, as well as a commitment to working with partners to identify further

targeted action. In parallel, the Building a Fairer City initiative mobilised employers, educational establishments, councils and other bodies to play their part in creating a more equitable London, targeting structural causes of inequality .

The London Health Board was quick to take on recommended action – appointing a champion for race equity to the Board. With a clear commitment to action across health and care partners – including the NHS, Integrated Care Boards, London Councils, ADPHL and the Mayor of London – a three-pronged approach to London action was taken forward Strategy, evidence and action. This programme was informed by the voices heard to date from a diverse section of London’s communities.

In 2023, the London partners published the Strategic Framework for Tackling Health Inequalities through An Anti-Racist Approach, an ambitious and action-focused framework setting anti-racist expectations for organisations at every level of health and care. To make sure the evidence for action was crystal clear. in 2024 The Institute of Health Equity, published their landmark evidence review – Structural Racism, Ethnicity and Health Inequalities in London . This review of evidence and interventions gave new voice to the evidence collected over many years by academic, health and voluntary and community sector partners about the importance of tackling racism as a determinant of health. “Tackle racism, discrimination and their outcomes” was cemented as the 7th principle in the well established “Marmot Framework” for action on health inequalities

Thirdly, was the investment in action. In November 2023 the London Anti-Racism Collaboration for Health (LARCH) was launched, with a focus on supporting and accelerating action across London health and care organisations to tackle health inequalities through embedding anti-racist approaches; turning evidence into action and supporting delivery of the framework Designed in coproduction with communities, the LARCH was developed signed to break down silos and improve collaboration between the people, service and structures that make up London’s health and care ecosystem, and accelerate action across the city. The LARCH will help to drive the anti-racist progress that is so desperately needed by Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic Londoners.